Crocidura suaveolens, the Lesser White-toothed Shrew , can be found across Europe and Asia, though it is not found in mainland Britain.

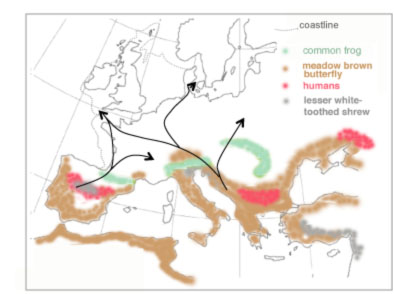

Since the last Ice Age, some shrew populations, including the Scilly shrew, have been isolated by seas and impassable mountain ranges.

With time, as DNA mutations accumulated in these isolated populations, they became different from each other, giving rise to different species and subspecies.

The genetic heritage of different subspecies of the Lesser White-toothed Shrew has been studied extensively, revealing a story of survival, isolation, hitch hiking and colonisation for all but one. The Scilly shrew is the missing puzzle piece that would complete the picture...

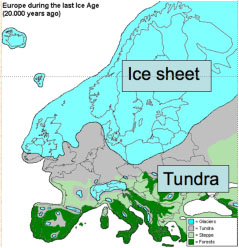

25000 years ago, Britain was covered by a massive ice sheet. The ice sheet reached the northern tip of Scilly and the weather was arctic.

In the most southerly parts of Britain some tundra species, like the St Martins Ant, were able to survive the arctic conditions.

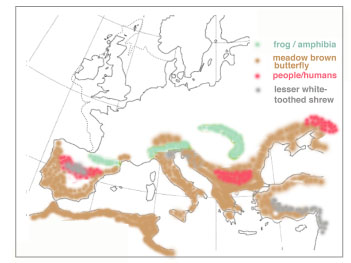

Whilst many species needing warmer temperatures became extinct, the Lesser White-toothed Shrew and other species survived in refuges around the Mediterranean and in North Africa.

Europe during the last Ice Age

Wildlife refugia around the Mediterranean basin, 25,000 years

before present

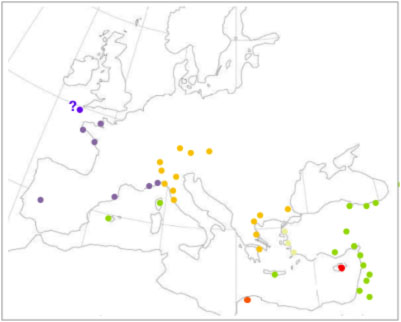

Just as we can find out our ancestry by sequencing our genes, comparing shrew DNA sequences tells us which shrew populations are genetically related.

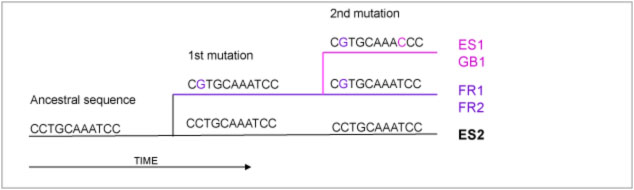

Looking at DNA sequences of modern flora and fauna we can find small differences, ‘mutations’ that tell us about the genetic history of the plant or animal. When populations of animals become isolated by seas or mountains and are no longer able to interbreed, their DNA sequences gradually become different from the original population as new mutations are added. We can use these differences to work out family trees (phylogeny) for living and fossil flora and fauna and chart their movements across the globe.

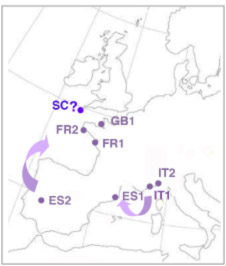

Each spot represents a shrew sample.

Different colours represent genetically distinct groups or 'clades' of lesser white-toothed shrew found across Europe.

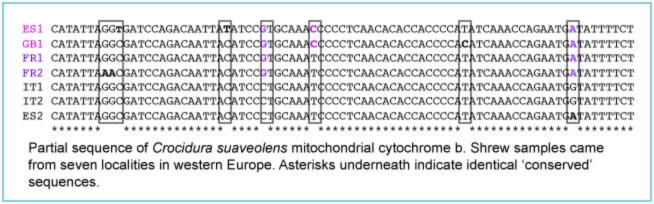

Sequence alignment:

Aligning the same piece of DNA from individual Lesser White-toothed Shrews collected in different localities shows where their DNA sequence differ.

Each line has a DNA sequence from the same gene but taken from different individual animals, collected in different locations.

Taxonomists divide these animals into two groups. Looking at

the sequences, do you think that ES1 and ES2 should be in the same

group, or not

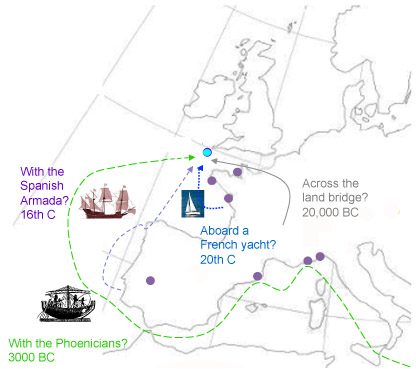

The DNA evidence suggests that the two Spanish samples, ES1 and ES2, come from populations that have been separate for longer than any of the other members of their group ('clade').

ES1 is more closely related to the Italian shrews, whereas ES2 is related to the French and Channel island shrews, suggesting that shrews from Spain’s Atlantic coasts may have travelled to Northern France and the Channel Islands with the Armada or with wool traders.

The arrows suggest trade routes that may have been responsible for dispersal of ‘hitch-hiking’ shrews in Western Europe.

Changes in DNA sequence ‘mutations’ occur all the time. Many

mutations have no effect on fitness, they are neutral- neither

advantageous nor disadvantageous and simply accumulate

gradually.

By comparing the mutations in different populations we can say which mutation appeared first and therefore which population became isolated first.

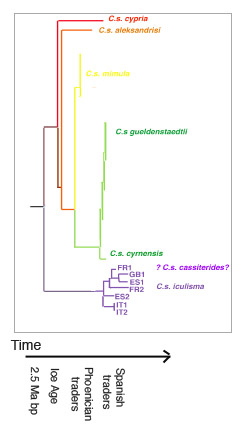

By working out which order mutations appeared in, we can

build an evolutionary tree of relatedness. Different shrew

populations or 'clades' are shown here in different colours,

corresponding to the shrew samples shown earlier on the map.

All the subspecies shown here evolved from a common ancestor that existed over 2.5 Million years ago.

The distribution of the ‘green' clade shrews in the Mediterranean islands and the Middle East, suggests that they were spread by Phoenician traders, 3500 years ago.

The ‘purple' clade was isolated from the other clades during the ice ages but its members diverged more recently -less than 3000 years ago.

Where does the Scilly shrew fit in?

DNA sequence data from the Scilly Shrew could tell us where the Scilly Shrew came from. DNA sequences similar to the 'purple' clade would suggest it came from France, Italy or Spain, whereas if it came by boat with the Phoenicians, its sequence would resemble that of the 'green' clade.

It is not known whether the Scilly Shrew dates back to the last Ice Age or arrived more recently. One possibility is that it derives from a small founding population introduced by man after Scilly became cut off from mainland Britain and Europe, but when did that happen?

To find out how and when the Scilly shrew arrived, we need to

collect and sequence DNA from Scilly shrews….

•Bannikova A A, Lebedev V S, Kramerov D A and Zaitsev M V. Phylogeny and systematics of the Crocidura suaveolens species group: corroboration and controversy between nuclear and mitochondrial DNA markers. Mammalia (2006): 106–119

Dubey S, Zaitsev M, Cosson J-F, Abdukadier A and Vogel P. (2006) Pliocene and Pleistocene diversification and multiple refugia in a Eurasian shrew (Crocidura suaveolens group). Mol Phylogenetics and Evolution 38 (3) 635-647

•Dubey S, Cosson J F, et al. (2007). Mediterranean populations of the lesser white-toothed shrew (Crocidura suaveolens group): an unexpected puzzle of Pleistocene survivors and prehistoric introductions. Mol Ecol 16(16): 3438-52

•Hewitt G. (2000) The genetic legacy of the Quaternary Ice Ages. Nature 405, 907- 913

•Petit R J et al. (2002) Identification of refugia and post-glacial colonisation routes of European white oaks based on chloroplast DNA and fossil pollen evidence. Forest Ecology and Management 156 (2002) 49–74

Scilly Shrew

The Scilly shrew is considered by some as a subspecies, named Crocidura suaveolens cassiterides - the “sweet-smelling shrew from the isles of tin”

As the climate warmed, Scilly, the rest of Britain and northern Europe were gradually recolonised by wildlife that had survived further south.

Recolonisation routes

Copyright © 2016 Creative Commons