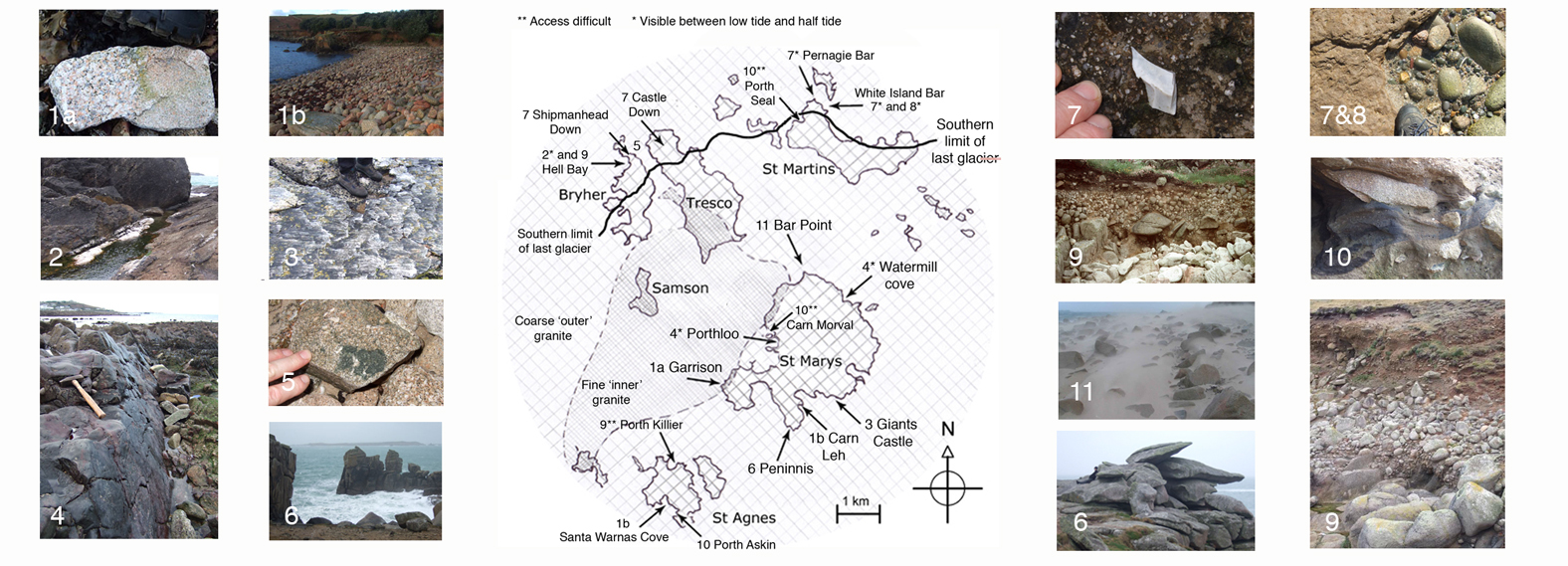

Map and guide to geological features visible around the islands. These features provide visible evidence of the events that have shaped the islands. Locations are given as Ordnance Survey grid references. Some features can be seen at more than one location.

Features 4, 5, 7 and 8 are only accessible at half tide and low tide - remember to check tide tables before exploring (HW and LW times are posted outside the harbour master's office on St Marys quay).

The granite pluton making up the bedrock of the islands formed in two phases. Differences in the cooling rate gave rise to the different textures of the fine-grained “inner” and coarser “outer” granites. Inner and outer granite bedrock can be seen on the Garrison foreshore off Charles' and Woolpack batteries respectively.

1b Colour of the granite

Granite is made up from three mineral groups, quartz (white), mica (black biotite mica in Scillonian granite) and feldspar (milky white). The colour of the feldspar mineral group in the granite varies in different locations. In some places, oxidation of trace iron present in feldspar mineral group within the cooling granite produced pinks and reds, seen in the granite at Carn Leh Cove, St Mary’s (SV913098) and at Santa Warna’s Cove, St Agnes (SV879078) .

Pebble showing both coarse, and fine grained granite, found near church quay, Bryher SV882153

Pink granite pebbles, Carn Leh Cove, St Mary’s SV913098

As the granite pluton cooled, quartz and tourmaline crystallized out along lines of weakness in the granite. In Hell bay, white quartz veins can be seen at low tide and half tide.

White quartz vein Hell Bay, Bryher, middle of frame, with breaking waves in background. SV874162

To the west of Giant’s castle, mats of quartz and tourmaline are visible from the path. The breaks or steps between the crystal mats show that the granite bedrock was under stress, and still somewhat fluid when these crystal mats formed

Stepped mats of fibrous tourmaline and quartz crystals between Porth Minack and Giant’s Castle, St Mary’s. SV918101

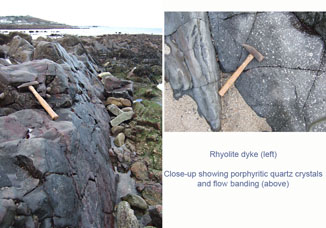

Movement of molten rock into a fracture in the granite formed the rhyolite and quartz-porphyry dyke at Porthloo. A similar feature can be seen at Watermill cove, and may be part of a single dyke cutting right across St Mary’s and extending southwest to Annet.

Rhyolite dyke Porthloo, St Mary’s, as seen at low water

looking WSW. SV907114

Little, if any of the sandstone “country rock” originally overlying the Scilly pluton is visible in situ. The molten granitic rock altered or metamorphosed the older sedimentary rock lying above it. This metamorphic rock is known locally as killas. As the Scilly pluton was intruded into the country rock, it engulfed pieces of this overlying sandstone, which formed xenoliths in the granite pluton. It is possible to find granite pebbles on the beaches containing these xenoliths.

A fragment of country rock incorporated into granite as a xenolith, found Bryher.

SV882153.

Granite outcrops around the islands have been shaped by erosive powers of wind, sea, and temperature change. Weaknesses developed in the granite pluton during uplifting and continental drift. Minerals filling lines of weakness often erode first, leaving deep clefts in the rocks. Peninnis has many tors showing prominent vertical clefts, and an outcrop, Pulpit rock, dominated by horizontal joints. Chemical weathering of the feldspar mineral group in the granite has produced some of the orange sediment layers locally known as “ram”, seen in cliffs and making up the subsoil. Other layers were brought here by glaciers or were blown from further north.

These are rocks that did not originate in Scilly, but were carried here as glacial deposits, moraines, from what is now the Irish sea. They include rocks of flint, red sandstone and siltstones, and range in size from boulders down to gravels. They mark the southerly limit of the last ice sheet to reach Scilly, around 20,000 years ago.

Clay-rich sediments lie under the boulder bar between White Island and St Martin’s. The clay contains coarse particles of erratics, including sandstone. These clay sediments also contain microscopic needle-like particles, spicules, of silica found in marine sponges, indicating that they were brought to Scilly in the last glacier, from a marine environment.

Raised beaches are visible in some of the cliffs around the islands as collections of rounded pebbles, often sorted by size, embedded in a matrix of fine sediments. The rocks in a raised beach have been worn smooth by the sea. Their presence as much as ten metres above current sea level, is evidence that sea levels have been higher in the past.

Evidence of arctic conditions in Scilly, 20,000 years ago, during the last Ice Age, comes from fossil pollen found in layers of ancient vegetation in some cliffs. The age of these plant parts has been determined by radiocarbon dating. Microscopic analysis of individual pollen grains identifies them as arctic, tundra, species.

Geological processes are not exclusive to the past, and although the timescale of the events described here is immense, some changes in drift geology can be seen from year to year. Much of the deep sand that covered Bar Point 30 years ago has moved as a result of erosion by winds, and tides and quarrying.

Granite tor showing block weathering, Peninnis, St Mary’s. SV913095

Siltstone errratic. White Island Bar, St Martin’s. SV924171

7 and 8. Glacial boulder clay with erratics, White Island Bar, St Martin’s. SV924171

Raised Beach, Porth Killier, St Agnes SV883085

Ice Age pond infills (left), with fossil birch pollen (top right) and fossil beetle wing cases (bottom right), Carn Morval, St Mary’s. SV906117

Aeolian erosion in a westerly gale (above), Bar Point, St Mary’s. SV915130

Copyright © 2016 Creative Commons